Peter Mitchell, the obsessive photographer of Leeds’ grimier streets over the last 50 years, is less well-known for his scarecrow pictures. He himself dismissed them as ‘snaps’ when his agent, Rudi Thoemmes, found a batch in a drawer. There are hundreds of them, often grabbed without permission (“Get orf my land!”) and now enshrined among Mitchell’s several, rather pricey books.

A few large scarecrow prints do occur in Mitchell’s current retrospective at Leeds Art Gallery (LAG). They are, though, readily overlooked in a display that recreates in its entirety the 81-year old’s 1979 exhibition ‘A New Refutation of the Viking 4 Space Mission’, along with a sizeable dollop of nostalgia-drenched prints which show the demolition of the once-famous Quarry Hill Flats, and a scatter-gun selection of historic commissions and more recent works.

But it was the scarecrows that set me thinking.

Scarecrows, whatever else they do, scare crows. They only need to dimly mimic the world’s most destructive ape; they don’t have to be overdressed, but it’s something we do anyway.

Photography, also, only needs to dimly mimic whatever Kantian soup is really out there; most of us happily substitute any shortcomings. In these digital days of tone mapping and AI enhancement, for instance, it is shocking to be reminded how slipshod ‘analogue photography’ could be.

Take Mitchell’s 1997 photograph of the memorial artefacts that were dumped outside Elland Road football ground after Billy Bremner’s death. The large gallery print is blurred, grainy and lacking any persuasive colour depth. You wonder that Art Transpennine, who commissioned the work, championed it at the time; especially as the original print was even larger.

But that’s a general point (…calculated to upset a generation of analogue adherents). More specifically, why – when there are so many locally devoted and obsessive photographers out there – do curators, critics and journos want to put their old clothes on the particular scarecrow that is Peter Mitchell?

Born in Eccles but brought up in Catford, Mitchell is variously termed a Mancunian or a Southerner depending on which chauvinism a journalist wants to tweak. He drove a delivery truck around Leeds when he settled there in 1972 and still gets called a ‘lorry driver’ (… as if the degree in silk screen printing and photography from Hornsea College meant nothing). He has since become the Cinderella of photographers; dependably turning from scabrous to glamorous whenever a Royal Ball is announced.

“After 40 years in obscurity meet Britain's most overlooked photographer…” headlined the Yorkshire Post in 2016. This was 20 years after that Art Transpennine commission and about the time that a national TV documentary was devoted to him. He had had major solo shows in both Leeds, York and Bradford and his work cropped up in one of Martin Parr’s exhibitions in New York.

We should all be so ‘overlooked’.

Mitchell (who is a hard man not to like) points out that his repeatedly buffed renown is Martin Parr’s ‘fault’. The Magnum-sized photographer of working class occiputs can be very generous with his fame and his remark about Mitchell’s aforementioned 1979 show at The Impressions Gallery (then located in York, now in Bradford) has been hugely influential, namely:

“This show was so far ahead of its time that no one knew exactly what to say or how to react, apart from with total bewilderment… It was the first colour show, at a British photographic gallery, by a British photographer.”

Most reviewers accept this claim uncritically; but it surely oversimplifies the history of colour photography in Britain and diminishes more pioneering souls like Tony Bulmer or Shirley Baker.

Not that it isn’t worth exploring Mitchell’s ‘colour status’. The reason why art photography came to be defined by ‘grainy, pushed Tri-X, monochrome prints’ was that it was cheaper and it lasted longer. Colour photographs needed longer exposures. They were more complex to process and to develop. And they faded.

Mitchell has always used subdued hues but you don’t hear much about why. Did he use Kodachrome, for instance, and if so how did he cope with its various formulas before it was discontinued in 2009? He remarks in one interview that the same technician developed his images for 40 years… but the information is otherwise scant.

Such scrutiny could raise uncomfortable questions. There is a definite sense that Mitchell’s work is now captive to a dead technology; that it verges more towards museology than aesthetics – which is not a problem for a ‘documentarist’ but could be for an ‘artist’.

How does Mitchell now feel about the chemical turquoise residue which rims the horizonal trees in his early images? Does he regret not buying a graduated density filter for his ‘Blad’ (i.e. Hasselblad) which would have repaired the bleached skies that look so naff? Would he even like to see their aerial corrugations and coruscations digitally restored?!

Mitchell seems the sort to skim over questions such as these. The ones who would object to them are those who attempt to critically exalt him – dressing the scarecrow in their own clothes.

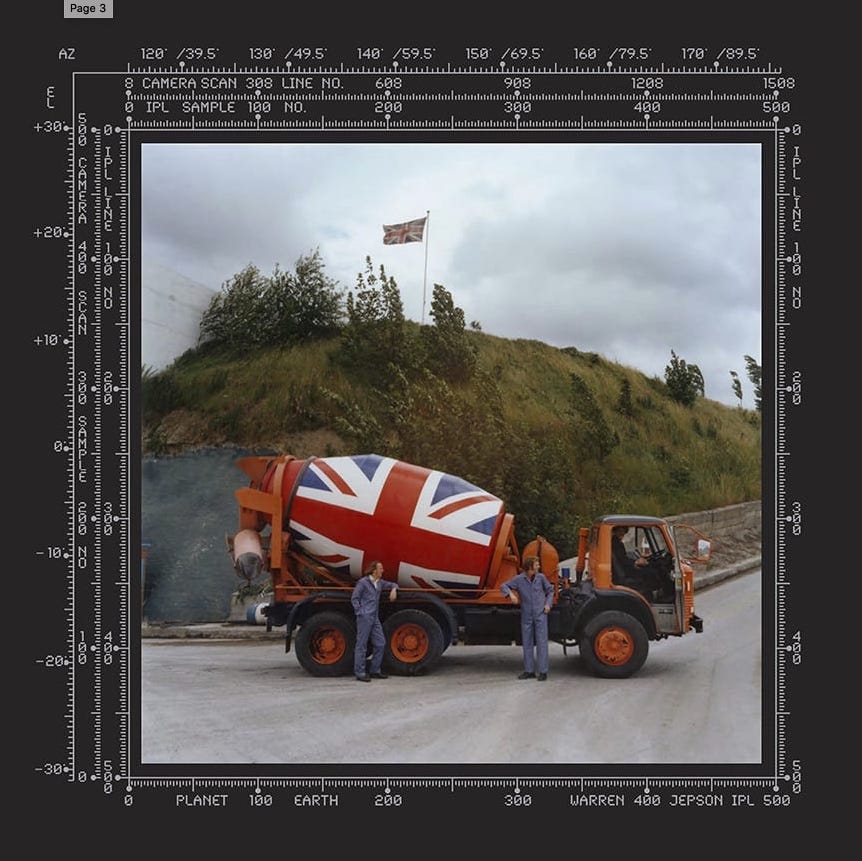

In his first shows Mitchell put his 7”x7” photos in red, metal frames ( …whether you’re talking spectacles or posters, the 1970s were not a good time for frames!). The ‘New Refutation…’ show additionally had calibrated surrounding mounts that replicated the graphics beamed back to earth from NASA’s Viking 4 Mars rover.

Here were 65 numbered photographs that reminded people of “the wonder of Planet Earth compared with the dusty deserts of Mars”. It was, whatever Martin Parr felt, not a hard concept to grasp: Mr. and Mrs. Hudson’s crumbling newsagents on York Road is more amazing than a mound of stone on a world without life. We should (impelled by the egalitarian spirit of the times) value it.

There are those, however, who want MORE. They emphasise that the title, ‘A New Refutation of the Viking 4 Space Mission’, is named after an essay by Jorge Luis Borges. Presumably ‘Nothing Lasts for Ever’ is likewise named after the action thriller novel by Roderick Thorp (… you know, the one that became the Bruce Willis movie, ‘Die Hard’).

They claim that the sequence of images in ‘A New Refutation…’ actually provides a narrative that is written in evolving hues and predictive spaces; as if Mitchell would or could spend days looking for a view that had a particular green, next to a skyline which anticipated the shapes in his next planned photograph.

The evidence suggests that Mitchell pieces his books and shows together on the editorial bench. There are three fine pictures of derelict swimming pools, for instance, which are variously dated over a 25 year period. He adapted images from his 1975 ‘breakthrough show’ in LAG’s Education Gallery for ‘A New Refutation…’ and – far from being a synthesis – they range in treatment from aspirational spontaneity (a biker gang clustered around, what I would probably wrongly guess, is a dilapidated Karman Ghia) to expectable landmarks (the Egyptian facade of Grattan Mills).

Better eyes than mine rate the sequence of Quarry Hill flats being demolished as the acme of Mitchell’s work. Me, I spent too many childhood days trespassing in abandoned Yorkshire buildings to be impressed by beleaguered sofas and meretricious wall paper. But Leeds has always clung to Quarry Hill – a failed pre-war experiment in social housing – like an adult cherishing a cheap doll from their childhood.

Surely the true ‘mission’ that answers Mitchell’s obsessions are when he gets the workers or owners of a business to stand in the doorway of their moribund properties and exude a proprietorial air. This could be my turn to be pedagogic: do these people own the building or does the building own them (groan)? But really, what strikes me is that Mitchell enjoyed the interaction (he used to give his subjects a small copy of the photographs he’d taken).

“For a moment or so,” he says “a rare occasion is created”.

Meanwhile, back in the gallery, the writing on the wall (…vinyl writing, that is; we’re not talking Belshazzar’s Feast) marches in step with each decade’s fashionable critique. The word ‘punctum’ crops up precisely where you expect it. The friction-motormouth himself, Geoff Dyer, spews forth in the ‘New York Times’. And the exhibition curators conclude by insisting that these are definitely NOT images of ‘a rare occasion’ but belong to “a continuous narrative of uncanny and uncertain context”.

One of Mitchell’s favourite subjects was Francis Gavan, a showman who for 20 years paid an annual visit to Woodhouse Moor with his ‘Tracked Dark Ride’ (a ghost train built by Orton & Spooner). If memory serves there is, here, a genuinely tragic narrative to be found; but it’s a journalistic one that seems to have evaded the curators.

To claim these are “iconic works from one of the most significant colour photographers of the late 20th Century” is simply misplaced hyperbole. An icon is something instantly recognisable to everyone within a culture, and Mitchell hasn’t produced such an image. But far from being a failing, this is the very source of his strength and appeal. These are ‘rare occasions’ not generic clichés and the merit of such work lies in its profusion not in its dominant exclusivity.

If the purpose of a review is to advise readers whether to go to a show or not then, certainly, drop by if you’re in Leeds. But don’t travel to Leeds specially for it. Use the money you save on a rail-ticket to buy one of Mitchell’s books. These are the natural abode for his work; offering as they do the profusion, the close contemplation and (of course) the fixity of litho printing.

‘Nothing Lasts Forever’ is ironically quite an extended show. It uses many works from the Leeds collection and has the feel of a cost-saving exercise. It is a paradox, given its renowned 19th C. watercolour collection, that LAG has never acquired a means of effectively displaying light-sensitive exhibits. The rooms are charmingly decked out with eccentric accessories that Mitchell has acquired over the years, but they are poorly lit.

You spend a lot of time dodging your reflection in glazed frames.

Which might seem an uncouth observation; but heck, photography usually IS vulgar. Or at least (to use a term that is in multiple ways pertinent to Mitchell) ‘vernacular’. When Mitchell’s images crop up on social media they instantly spark a firework display of memories; about the health and safety standards during the demolition of Quarry Hill Flats, say, or nauseatingly fond recollections of long-lost workplaces.

Mitchell once corrected someone who tried to refute the idea that his images were sentimental. “Oh they are,” (I paraphrase) “but it’s a hard-edged sentimentality” he said. It was good to see the scarecrow fight back.

‘Nothing Lasts Forever: Peter Mitchell 1972–2024’ continues at Leeds Art Gallery until 6th October 2024. The exhibition is free but DO note that it is not open on Mondays. Martin Parr is set to interview Peter Mitchell at the Hyde Park Cinema on August 9th, but the event is said to be sold out. Guided tours of the exhibition by Peter Mitchell are listed but also tend to sell out and should be booked in advance.