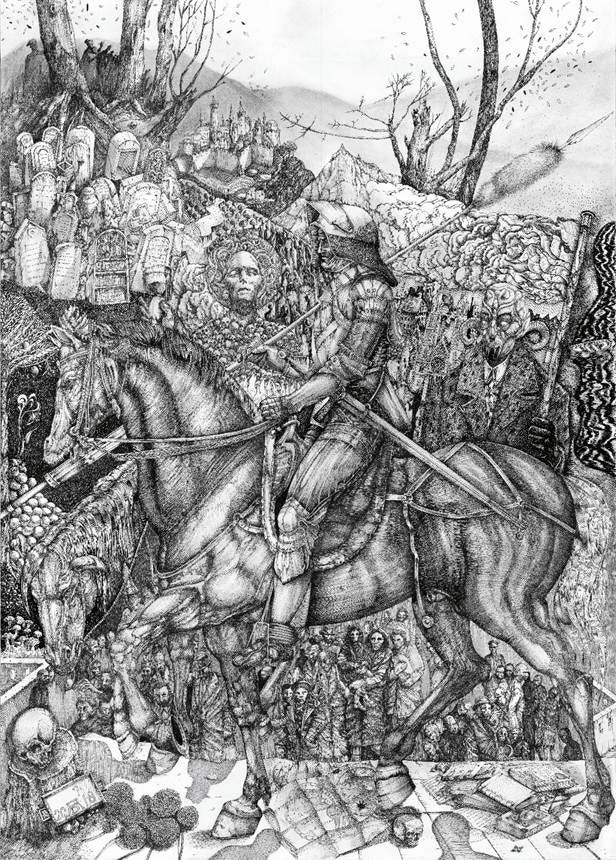

The knight, death and the devil. Albrecht Durer (1513) and a reinterpretation by George Sfougaras (2018). Currently on display at the Museum within the German Expressionism permanent collection.

There’s nothing quite like a reinterpretation to focus the mind. A recent event, organised by Leicester Museum and Art Gallery, New Walk, to mark Holocaust Memorial Day, provided such an opportunity. Artist, George Sfougaras, reinterpreted an engraving by Albrecht Durer. He explained some of the background to the original, its use by the Nazis as part of their propaganda efforts and his own reflections on the looking at the image today.

Comparing similarities and differences has been a rewarding, fruitful and interesting exercise and has raised some interesting questions for further exploration around the use of symbolism in art for today compared to its use in the past.

The original image, created in 1513 by the peerless artist, Durer, from Nuremburg, Germany, is an exquisite engraving depicting a knight entering the valley of the shadow of death (psalm 23).

The composition is rich in a symbolism that would have appeared everywhere in Durer’s time – being heard or read in scripture or woven into paintings, prints, carvings, wall-hangings and sculpture that decorated the floors, walls and ceilings, inside and out, of churches and buildings - ecclesiastical, public and domestic. Durer’s image is one of the high points of Renaissance and was created during a momentous historical period. It was an era where military conflict had been playing out over centuries across Europe and beyond and was just teetering on the brink of an era of greater turmoil yet to come. Institutions and ideas were being challenged and were in a great state of flux. In this context, Durer’s image can be interpreted in many ways.

For Durer, suffering would have been keenly felt and deeply personal. He was one of just two siblings surviving from eighteen brothers and sisters. Plague was rife, as was military and political conflict. Is Durer’s knight resolute in his forward stare, accompanied by his faithful dog and carried forward by the strong horse? Do these three figures combine to inspire people to resist the temptations of sin coming from the body, the Devil and the world, a resistance advocated by the scholar and humanist, Erasmus? Is the warrior knight acting out the courage and sacrifice required to attain the virtues of Faith and fortitude? Or has the Knight been cut down to size through losses such as those experienced by the Teutonic knights of this time or by his inability to reconcile the role expected of him by the Church to be a warrior knight, slaying the enemy whilst trying to reconcile the teachings of scripture on what it means to be a good Christian. Or maybe he is a mercenary or robber. Each scenario would alter the knight’s resolve and make his destination less certain, but it would surely have been on to a more secular world beyond.

Already dizzying from the sheer detail and possible meanings represented within the Durer, Sfougaras’s reinterpreted drawing challenges you to consider another set of images, metaphors, analogies and symbols.

Sfougaras’s image calls to mind how the Nazis marshalled Durer’s Knight in the service of their propaganda; aiming to galvanize and fortify the German people in a quest for unification and expansion. The knight is transformed into Teutonic guise, not by a change to his amour, but through the introduction of new imagery – the hillside strewn with Jewish and Muslim graves; the faces of the millions of people, murdered or with disrupted lives (including those of Sfougaras’s relatives depicted in the drawing). The Devil is no longer threatening time with his hourglass but is, himself, starving and sickly. And again, Nuremberg is in the background – an Imperial city, a site for Nazi rallies, the origin of race law creation…and the location of the Nazi War Crime trials. Sfougaras would also like us to see the figure as a stand-in for parallels with events of our time – for all dislocated people, for all hated groups, for all holocausts.

A couple of examples from his image help us explore his use of imagery.

Flag - A national flag has generally symbolised an important and necessary sign used in battle, differentiating combatants, or it can serve as a rallying point for a community or nation. But here the devil’s flag is in flames, providing an ideological marker of a place where you’re likely to find haters sowing division rather than unity.

Books - Sfougaras introduces a pile of books being trampled underfoot by the knight’s horse. Books are often used symbolically in religious and secular art and may signify types of knowledge or learning associated with a particular virtue, but they can also represent a specific historical or mythological figure. The meaning of the symbol will be given using additional markings denoting what the book is, the context within which it is placed and the function it is given. In this drawing, it is not clear if the knight is unaware of, or is actively carrying out, this vandalism. Either way, there is no possible virtue in the actions of the knight; he will only be viewed by the audience in a dim light. The books stand in for the forgotten lessons of history, a shorthand for ‘never again’. But what lesson are we being taught in these books? The origins of the holocaust and its unique barbarity has morphed into a simplistic notion of ‘hate’ applicable to any routine atrocity. The horrific nature of war and conflict cannot be collapsed into the attempted extermination of a whole people. Given the contest over this history, the symbolic use of a book telling a simple truth is problematic.

The knight - In art, the knight, as warrior and soldier, fights for causes, metaphorical or literal. The knight of Durer’s time will have ‘hated’ his enemies in the original sense of the word i.e. confronting adversaries (symbolic or real) who meant harm to his faith or to him. The humanism of Durer’s moment was that through the exploration of the personal character, the individual’s idea of self-knowledge also expanded; marking another moment in the transformation of what it means to be human. The Nazi knight, used as propaganda, is a one-dimensional cut-out; obliterating the individual character of the knight, which, in turn, led to the dehumanisation of his adversaries - taking away their flag and destroying their books. And in the context of today, is it the activist, the progressive, the conspiracy theorist, the patriot, the victim, the influencer or the petty criminal, who is given a face or assigned to wear the face and body of the Devil; a de-humanised and repugnant animal? Again, these matters are not settled and widely contested.

Sfougaras’s images seem to act as warning signs about the evils of the world, providing a kind of stop sign for the viewer, serving more as a work of education rather than an aesthetic experience created by a contemplation of the whole.

The images being more literal than symbolic, ironically, provide less space for the audience to reflect on the moral ambiguities within the composition. Instead, it seems to tell a particular story, aiming to be a carrier of evidence for use as warnings or of judgement.

Virtue - The notion today that striving towards a virtuous ideal through practising courage, honesty, etc., has become quite alien. Any framework for moral thinking has been dropped or is too simplistically drawn. The idea of not hating and being kind leaves no room for ambiguity. As soon as these ideas encounter a real person, any ambiguity of meaning or intent quickly descends into judgement – but of an intolerant kind. It’s not that people don’t strive to live honourably (whatever that may mean to them), but that there is no clear idea of what virtue means. Not hating has been perverted to mean ‘any mean idea towards anyone’…which falls apart as soon as you meet someone you disagree with. Any scope for sympathy or genuine empathy is possible within such general definitions.

This makes the question of symbolism within art today a very difficult, but also interesting and necessary one to explore. It matters in terms of how we make sense of art and imagery and also how it functions in contributing to a coherent aesthetic experience of the viewer.

The juxtaposition of these two images was a fascinating idea and this certainly provides a very helpful comparison when considering art in our changing times.

Jo Herlihy

References:

Dictionary of subjects and symbols in art. James Hall. 2nd edition. 2008. Westview.

The wheel of virtue: Art, literature, and moral knowledge. Noel Carroll. The journal of aesthetics and art criticism. Vol. 60. No.1. winter 2002. Pp. 3-26

The Knight, Death and the Devil by George Sfougaras (2018) is on display at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery until 28th February 2025. https://www.leicestermuseums.org/HMD-2025